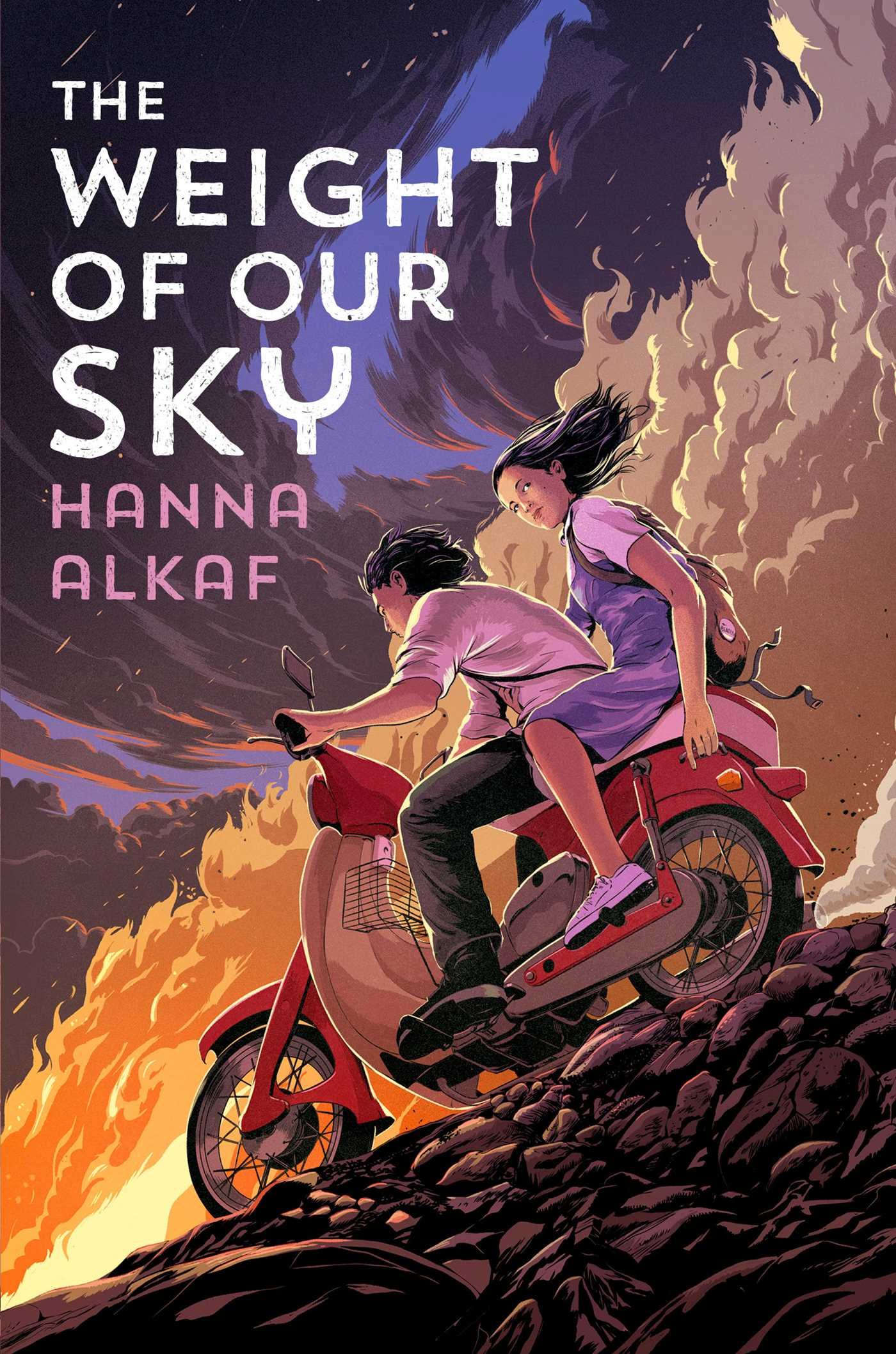

The Weight of Our Sky: Faith and OCD

The Weight of Our Sky follows Melati, a Muslim Malay teenager with OCD, in the midst of the Malaysian race riots of 1969. Melati has been battling intrusive thoughts from the Djinn living in her mind for years, which involves a series of number-based compulsions in order to keep it at bay. But when the riot begins, she’s confronted with a danger she isn’t able to control or keep at bay on her own. Mel must confront the hostile forces both outside and inside her mind to reunite with her mother.

Filled with heart from beginning to end, The Weight of Our Sky is a gripping coming of age story that treats its inclusion of OCD with a touching amount of care. As someone with OCD, despite the many differences between the protagonist and me, I felt seen from the first page I read. The writing structure displays just how “intrusive” intrusive thoughts can be, and how they can send you into a spiral at any moment. The way these thoughts were displayed among experiences of everyday life was very representative, as well as the shame associated with them.

I recommend The Weight of Our Sky to anyone, both with and without OCD. However, it covers deeply triggering topics of OCD and violence in general due to its setting and the nature of Mel’s intrusive thoughts. Reading it was a deeply impactful experience. If you’re in the headspace to engage with that, I highly recommend it.

Melati never once calls what she has OCD, nor is she diagnosed with it at any point. This article analyzes the impact this has on her and her relationships, as well as the stigma surrounding her condition. This is not a condemnation of Melati, her community, or anyone else within the narrative. For one, this is set in 1969. OCD, as a term, was not coined until the 1980s (When Was OCD Discovered? A Brief History of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder – OCD Mag), although it had been known by other names previously. There was no way for anyone in her life to know of this term and the associated diagnosis.

Her experiences and her responses to them are no less valid because she wasn’t able to be officially diagnosed. However, the rise in understanding of OCD and popularization of the term has allowed for communities to be formed, appropriate treatments to become more readily available, and stigma around intrusive thoughts to be reduced. It is no fault of Melati or anyone else in her life that she did not have this diagnosis. However, it’s useful to discuss it as a means of education on differences in lived experience.

One of the central relationships in The Weight of Our Sky is that of Melati and her mother. Their relationship is mostly shown through flashbacks, as they are separated for the majority of the narrative. Melati’s mother is her sole caretaker, and clearly impacted by her daughter’s disorder. For a long time, she searches for some way to cure this.

Intrusive thoughts are ego dystonic. This means that they are opposed to one’s sense of self. This is more obvious in something like harm obsessions, where someone may avoid knives because of intrusive thoughts about hurting someone, but it’s true in other types of obsessions as well. For example, someone with contamination obsessions does not clean because they enjoy it. It is possible that they do, but that is a trait independent of their OCD. They clean against their own will, because they cannot stop worrying about what will happen if they don’t. The compulsion brings temporary relief at the prevention of their intrusive thought becoming reality. In The Weight of Our Sky, this is seen in Melati’s counting behaviors that she finds no joy in, but does as a method of coping with the thoughts that the Djinn shows her.

The ego-dystonic aspect of intrusive thoughts is, unfortunately, still not well known. If there is a stigma around them in the present, there most certainly was a stigma in 1969. Shame has been and continues to be a significant component of OCD. This is especially true in cases of harm and religious-based intrusive thoughts, although it can happen outside of that as well. Shame over intrusive thoughts can be a leading drive for compulsive behaviors and not seeking treatment. In a 2015 study, Weingarden and colleagues said:

A small research base also supports the assertion that shame leads people with OCD to avoid disclosing symptoms. In an Internet study of 175 participants meeting self-report OCD criteria, 58.2% indicated that feeling “ashamed of needing help for my problem” acted as a treatment barrier, and 53.2% indicated that feeling “ashamed of my problems” acted as a treatment barrier … more participants indicated that they would hide religious or aggressive symptoms (i.e., those that may be most shame-laden) from family and co-workers (Beşiroğlu et al., 2010). Thus, shame in OCD may promote social withdrawal, in addition to acting as a treatment barrier.

We see this very clearly in The Weight of Our Sky, where Melati hides her intrusive thoughts from everyone and learns how to disguise her compulsions as fidgeting or harmless habits in order to keep from being discovered. Some continuation and segue into journey from cure to acceptance

When I read this story, one of the first things that came to mind was “Ideology of Cure” by Eli Clare, from his book Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure. “Ideology of Cure” talks about how the prioritization of cure feels as a disabled person seeing resources that could have gone to making life easier through building ramps, funding access to wheelchairs, etc. instead go into research for a “cure” he doesn’t even want. Mel does want a cure. She wants the Djinn to leave her alone and let her live in peace. Despite this, she feels equally pressured and minimized in the search for a cure. She grows disillusioned with the many people she’s brought to meet. Eventually, she fakes cure while suffering alone simply to make her mom happy. She cares deeply for her mother, which is not a bad thing. However, it is an example of how her experience of “cure” never prioritized her wellbeing, just the appearance of wellbeing.

However, this does not mean that healing is impossible or an inherently bad thing to seek out. In many ways, Mel has healed by the end of the story, despite the Djinn remaining within her.

Over food, our talk turns to story. My friend P. tells us how she’s been encouraged in dozens of ways to think about her life with cancer as a battle. She says, “I’m not at war with my body, but at the same time, I won’t passively let my cancerous cells have their way with me.” We talk about healing and recovery, surviving and dying. No one invokes hope or overcoming. (Clare, “Ideology of Cure”, page 13)

None of the attempted cures work. None of the visits to doctors and practitioners bring her any peace, and instead leave her more hopeless that a way out is possible. Instead, she makes progress slowly and painstakingly. Her process is a slow rebellion against the Djinn and its methods of controlling her.

Everybody who’s around you gets hurt, the Djinn says warningly. You’re toxic, Melati. You’re capable of protecting nothing and no one. You’ll get this girl killed, just like you got Saf killed. The mention of Saf’s name sends a stabbing pain shooting through my chest, and I waver for an instant. Then I feel a little hand work its way into mine. May looks up at me trustingly, and I know right then that there is no way I’m leaving without her. “That’s right,” I tell her. “I’m going to get you out of here, and we’ll find a way to get you home.” (Pages 232-233)

At first, the language of calling it her Djinn broke my heart. It seemed like such an isolating way to feel about something that lives within you. I felt horrible for the trauma she had endured and the stigma she would continue to experience due to this assignment. Upon reflection, I think that was the wrong way to think about it. For one, I realized that despite the difference in the language we used about our conditions, our journeys to equilibrium felt close to identical. At first, there’s shock and shame surrounding the thoughts. Then, an effort to seek help and treatment. Then facing the realization that it will likely never go away completely, and then learning to live despite that.

Mel and I live very different lives in very different times. And although I do think my time and nomenclature allowed me to experience less stigma in my process, that can be credited to my very specific community as well, which has always been deeply supportive of me. I am sure not everyone in the world right now experiences the same, even if they are diagnosed correctly. It’s wrong to diminish Mel’s knowledge and expertise in her lived experience just because we call it by different names.

I’ve come to accept that the Djinn and I are always going to be locked in a battle for control of my brain and my body, that he will never truly go away and leave me in peace. But I also know now that I’m capable of fighting these skirmishes with him each day, and that more days than not, I’m capable of winning them. (Page 273)

Mel found the answer all on her own, without any outside knowledge of her condition. She learned how to be in relationship with her Djinn. She didn’t need the language of OCD to find that. The story doesn’t end with a diagnosis, and it doesn’t end with a magical cure. It ends with acceptance of who she is, and that she will live on regardless.

The Weight of Our Sky is a beautiful journey from trauma, to failed cure, to a slow, difficult reclamation of Mel’s life. It’s touching in its sincerity and complexity. Every character feels real in their motivations and actions, even if you don’t agree with them. Mel’s journey was admirable and relatable, and the connection I had to her character from the first page only grew stronger as the story progressed.

Before I end this, I also want to specifically mention the reason I initially chose this for my first noteworthy representation piece. As of when I’m writing this in November of 2023, The Weight of Our Sky is the one of four pieces of media in my database depicting a person of color with OCD, only two of which have been confirmed to be intentional representation. Although this is certainly a phenomenal story, I wish that it was one of many more examples I could point out to depict a range of people and cultures experiencing obsessive-compulsive symptoms and normalizing that lived experience. I am so grateful that I read this story, because it absolutely broadened my perspective and forced me to confront some of my own biases in regards to OCD and religion. I hope that in the future, it is one of so many more examples of this. I highly recommend that all of you buy this book and support the author, as well as to embrace the chance to learn more about what OCD can look like outside of a modern Western perspective.