The Hospital Suite: OCD and Trauma

The Hospital Suite is an autobiographical comic depicting Porcellino’s experience in the hospital during a series of traumatic injuries, as well as the impact it has on his life once he leaves. He describes his experience with multiple types of obsessions, primarily contamination and scrupulosity. The multifaceted nature of OCD is something I have highlighted in my own work, through choices such as having a main and secondary category for obsessions and compulsions to allow for more than one obsession or compulsion to be represented within the same work. Dr. Keara Valentine, a clinical assistant professor at Stanford University, says this:

You can absolutely have two or more different types of OCD. Some people only have one subtype, but it is definitely common for people to have more than one. Over time, the subtypes may change or stay the same. In some cases, there tends to be one specific type of OCD that presents itself throughout a person’s life, with various symptoms changing over time. In other cases, people manifest different subtypes at different points in their lives. For example, “just right” OCD as a child, contamination OCD as an adolescent, and harm OCD as an adult.

So, although it is not always depicted as such, OCD is a fluid condition that can evolve alongside the individual experiencing it. This is how I have personally experienced OCD, as something that changes over time. And yet, this is not how OCD is generally depicted in media. In As Good As It Gets, Jack Nicholson is unchanging, obsessive in all of his pursuits in a singularly unkind way. The movie treats his OCD as though it is a character flaw akin to severe stubbornness, and when he has his transformation in personality by the end of the movie, his OCD miraculously vanishes once he becomes a better person. Although OCD can ebb and flow over time, it is not because it only appears when you are a bad person and disappears when you become better. The movie is a clear mischaracterization of what it is to live with OCD. Although Dirty Filthy Love is successful in its portrayal of how OCD can interact with other disorders such as Tourette’s and ends the movie with Mark Furness still having OCD, his OCD is still singular in presentation.

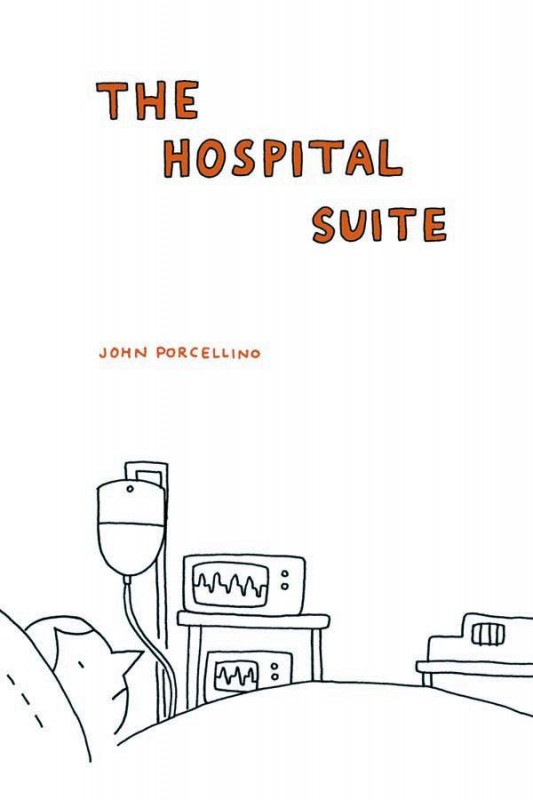

Contamination OCD can take many forms, but it is primarily the fear of contamination of self and others. This singular nature of OCD representation is especially apparent within works depicting contamination obsessions, as seen in Monk, The Aviator, Kissing Doorknobs, Scrubs, and Whitechapel. I was delighted to find an exception to this in The Hospital Suite by John Porcellino.

Another important point brought up by The Hospital Suite is the way that OCD interacts with trauma and PTSD. OCD is brutal on its own. But given trauma to fuel its facade that the actions and thoughts it encourages are not only rational but the only way to avoid the tragedy someone has already experienced once, they become overwhelming. A study by Wadsworth and colleagues in 2021 reviewed the connection between OCD and trauma.

Mental contamination appears often in both the trauma and OCD literatures indicating it may be a link between trauma-related disorders and OCD. Decades ago, Rachman (1994) explained the concept of mental pollution, suggesting individuals experience an internal sense of uncleanliness following direct or indirect contact with something that is considered “polluted.” In more recent literature, this term has been refined and is now often referred to as mental contamination, which furthers the earlier definition by suggesting the internal unclean sensation is brought on by human sources of violation, abuse, or adversity (Rachman et al., 2012). Due to the suspicion that mental contamination is human caused, and not thought to be caused by unclean inanimate objects, researchers have begun investigating the presence of mental contamination in both OCD and PTSD following exposure to adverse experiences … Taken together, these findings indicate that mental contamination may be an underlying factor in cases of comorbid PTSD and OCD following trauma—particularly if the traumatic event was human caused, as was the case in these experiments.

In the case of Porcellino, his traumatic experience caused literal contamination obsessions, making him spiral into fears about contaminated objects and coming into contact with something contaminated. In terms of mental contamination, Porcellino is also overcome by the fear that all of the pain he has experienced is because God is punishing him, and thus he must never do anything worthy of punishment. So despite the fact that his experiences are not “human caused” in the way Wadsworth and colleagues explain, he has determined that his experiences are something that God has done, and therefore are Porcellino’s responsibility through his sins. He becomes overwhelmed with the need to only do the “right” thing in every situation, something which is challenging even if you can consistently determine what the right thing is. Often in the book, we see him so overwhelmed by what choice is the correct one that he cannot bring himself to make any choice at all.

There is a great example of this on page ADD NUMBER, where he depicts himself panicking over a bag of groceries after the cashier sneezed on it. The food is contaminated now, so he can’t eat it. But wasting food is a sin, and if he wastes food, God will hate him. He could give it to a food pantry. But what if they get sick because of him? No, they won’t, there’s not even anything wrong with the food. But shouldn’t he just eat it himself, then? But what if it’s contaminated? And so on. It is not just that he experiences both physical and mental contamination, both contamination obsessions and scrupulosity obsessions, it is that they work together in a way that counters the compulsions that would have soothed the other. Although the compulsions are not a healthy solution, they offer a brief reprieve from the onslaught of intrusive thoughts. With both of them in play, he is not even afforded that, instead stuck in a cycle of rumination that never ends.

Although labels like contamination can help us put a name to our struggle, no people with OCD experience the exact same set of obsessions, compulsions, and lived experiences generally. OCD is a reactive disorder that changes with you, and works that depict that are essential to increasing understanding of OCD as a whole. The Hospital Suite is a genuine, thoughtful, and compassionate dive into what OCD looks like in day-to-day life. It’s thought provoking and compelling, a deeply individual story that still speaks to me as a person with OCD. I highly recommend reading it for yourself.